When we think about abuse, we often picture bruises or broken bones. But some of the most devastating wounds aren’t visible at all. Emotional abuse – especially gaslighting – is one of the most insidious forms of control used in both domestic and sexual violence. It doesn’t leave physical scars, but it can distort a survivor’s sense of reality, erode their confidence, and leave them questioning their own thoughts, feelings, and memories. May is Mental Health Awareness Month – so we wanted to take the opportunity to talk about how devastating the effects of emotional abuse can be on someone’s mental state, and how it can silently unravel a person’s well-being over time.

I’m sure by this point you have heard the term “gaslighting” used in conversation (or seen it on social media). The term has been casually used to describe a situation when someone is not telling the truth. It, however, is much more detrimental than just another form of lying.

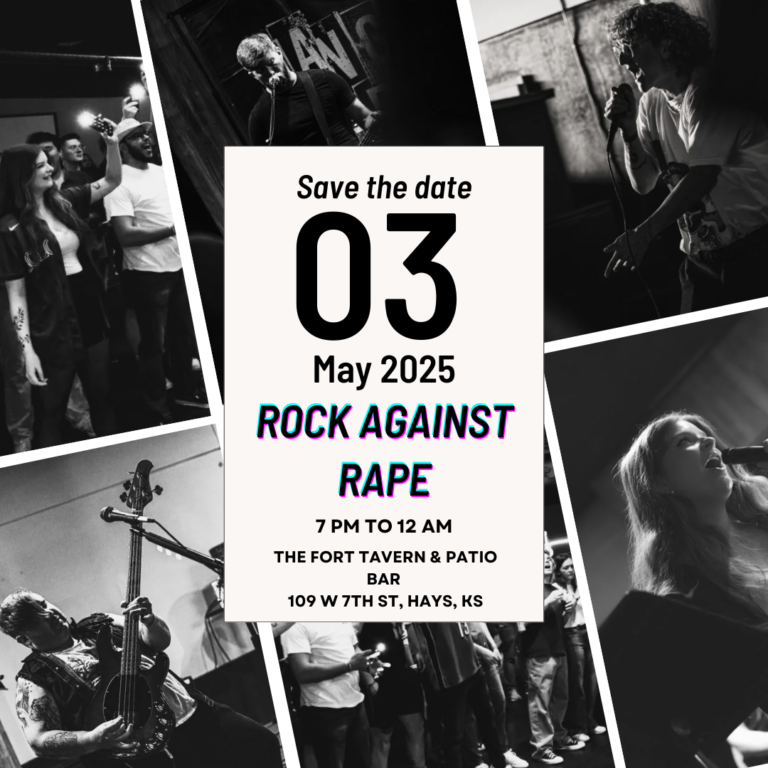

Over time, gaslighting can dismantle a person’s mental health from the inside out. Gaslighting is a tactic of psychological manipulation in which one person tries to make another doubt their perceptions, memories, or sanity. It’s not always easy to identify, especially in the beginning. It may start with small comments like, “You’re remembering that wrong,” or “You’re too sensitive,” and gradually escalate to full-blown denial of events, blame-shifting, or rewriting history. In abusive relationships, gaslighting is used to maintain power and control. It is used to keep the survivor dependent, confused, and isolated.

Imagine living with someone who constantly tells you that your feelings are irrational, your memory is flawed, or your concerns are overreactions. Over time, you may begin to wonder: “Maybe I really am too emotional. Maybe I am the problem. Maybe I don’t trust myself.” This kind of emotional manipulation breaks down a person’s self-trust and replaces it with self-doubt, shame, and anxiety.

Many survivors of domestic or sexual violence report feeling like they’re “going crazy,” when in reality, they’re responding appropriately to an unsafe and controlling environment. Gaslighting makes that response feel wrong or invalid. It causes a deep rupture in mental health – one that can look like depression, confusion, low self-esteem, and even post-traumatic stress. People who’ve experienced gaslighting may struggle to make decisions, trust others, or even recognize abuse when it happens again.

Many survivors of domestic or sexual violence report feeling like they’re “going crazy,” when in reality, they’re responding appropriately to an unsafe and controlling environment. Gaslighting makes that response feel wrong or invalid. It causes a deep rupture in mental health – one that can look like depression, confusion, low self-esteem, and even post-traumatic stress. People who’ve experienced gaslighting may struggle to make decisions, trust others, or even recognize abuse when it happens again.

Gaslighting also works hand-in-hand with coercion. Coercive control is about dominating another person through psychological manipulation, isolation, intimidation, and micromanagement of their life. Together, coercion and gaslighting create a trap: the survivor feels unable to leave, unable to speak up, and unable to trust their own ability to assess danger. It’s like being in a mental maze with no way out.

So how do you recognize gaslighting when it’s happening? Some common signs include:

So how do you recognize gaslighting when it’s happening? Some common signs include:

- Constantly second-guessing yourself or your memories

- Apologizing all the time, even when you’re not sure why

- Feeling confused or “off” after conversations with your partner

- Being told that you’re “too emotional,” “crazy,” or “making things up”

- Not being able to trust your instincts

- Withdrawing from friends or loved ones because you’re afraid they’ll see the truth, or because your abuser says they’re “bad influences”

It’s important to understand that gaslighting isn’t just a communication issue – it’s abuse. It’s not about miscommunication or a difference in perspective; it’s a deliberate strategy to destabilize and control.

But as overwhelming as it can be, there are ways to begin reclaiming your reality and your mental health. One of the first steps is naming the behavior for what it is. Giving it a name – gaslighting – can be incredibly powerful. It tells you that you’re not imagining things, and that others have experienced it too. It also affirms that your confusion is not a personal failure, but a symptom of emotional abuse.

Documentation can also be a helpful tool. Keeping a journal, even just jotting down events and how they made you feel, can help you reconnect with your own memory and intuition. Reading your own words back can provide clarity over time and remind you that your experiences are valid.

Talking to someone you trust (a friend, a therapist, or an advocate) can also break the isolation that gaslighting creates. When someone else can affirm your experience and help you untangle what’s happening, it’s easier to rebuild your sense of self. If talking feels too hard, even reading survivor stories or forums online can help validate your experience and reduce the sense of being alone.

Perhaps most importantly, healing from gaslighting means learning to trust yourself again. That’s not something that happens overnight. It starts with small steps: trusting your gut on something minor, saying “no” when you mean it, recognizing red flags, or even just noticing when someone tries to make you feel small. Each step builds a little more confidence. Over time, survivors can learn to see gaslighting for what it is: a manipulation tactic, not a reflection of who they are.

Gaslighting messes with your mind in ways that are deeply damaging, but healing is possible. Survivors deserve support that honors their truth and affirms their reality. Mental Health Awareness Month is a good time to remember that emotional abuse is abuse, and that psychological wounds deserve just as much care and recognition as physical ones. No one should be made to doubt their worth, their experience, or their sanity at the hands of someone who claims to love them.

If you need any additional information, have a question, or a concern, feel free to reach out to Options at our 24-hour toll-free helpline 800-794-4624. You can also reach an advocate via text by texting HOPE to 847411 or click 24-Hour Chat with Options.

Written by Anniston Weber

This grant project is supported by the State General Fund for Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault, sub-grant number 25-SGF-07, as administered by the Kansas Governor’s Grants Program. The opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Office of Kansas Governor.

Ellis County Community Forum

Ellis County Community Forum  What Were You Wearing? Art Exhibit

What Were You Wearing? Art Exhibit  Walk a Mile in Her Shoes

Walk a Mile in Her Shoes  Red Flag Garden

Red Flag Garden Spring Art Walk and Hays High School Student Advisory Bake Sale

Spring Art Walk and Hays High School Student Advisory Bake Sale

Reproductive coercion refers to behaviors that interfere with a person’s reproductive autonomy, including:

Reproductive coercion refers to behaviors that interfere with a person’s reproductive autonomy, including: Why does pregnancy increase a person’s risk of homicide? There are several possible factors:

Why does pregnancy increase a person’s risk of homicide? There are several possible factors:

The alleged harassment of Lively took place during the production of an ambitious project directed by Justin Baldoni. The film, touted as a groundbreaking exploration of complex gender dynamics, drew early praise for its vision but quickly became a lightning rod for criticism due to the nature of the topic: domestic violence.

The alleged harassment of Lively took place during the production of an ambitious project directed by Justin Baldoni. The film, touted as a groundbreaking exploration of complex gender dynamics, drew early praise for its vision but quickly became a lightning rod for criticism due to the nature of the topic: domestic violence. Angelina Jolie’s experience offers a chilling parallel. During her tumultuous divorce from Brad Pitt, Jolie alleged domestic abuse. Instead of being met with empathy, Jolie became the target of a PR campaign portraying her as a manipulative, alienating figure. The focus shifted from Pitt’s alleged abuse to Jolie’s parenting, mental health, and alleged vindictiveness.

Angelina Jolie’s experience offers a chilling parallel. During her tumultuous divorce from Brad Pitt, Jolie alleged domestic abuse. Instead of being met with empathy, Jolie became the target of a PR campaign portraying her as a manipulative, alienating figure. The focus shifted from Pitt’s alleged abuse to Jolie’s parenting, mental health, and alleged vindictiveness. While Meghan Markle’s case doesn’t involve an intimate partner, it highlights another facet of this pattern: institutional abuse. Markle, the first woman of color to marry into the British royal family, faced relentless media attacks fueled by leaks from palace insiders. When Markle publicly discussed the racism and mistreatment she endured, the narrative quickly shifted.

While Meghan Markle’s case doesn’t involve an intimate partner, it highlights another facet of this pattern: institutional abuse. Markle, the first woman of color to marry into the British royal family, faced relentless media attacks fueled by leaks from palace insiders. When Markle publicly discussed the racism and mistreatment she endured, the narrative quickly shifted. Heard’s experience set a dangerous precedent, demonstrating how powerful men can manipulate public opinion to protect their reputations. This blueprint has since been replicated, from Jolie to Markle and now, allegedly, Lively.

Heard’s experience set a dangerous precedent, demonstrating how powerful men can manipulate public opinion to protect their reputations. This blueprint has since been replicated, from Jolie to Markle and now, allegedly, Lively. Abuse is about power and control, not about how “nice” someone is. Truly, all the women mentioned in this blog post could be bratty, snotty, snobbish women. But that doesn’t mean that they should become victims of abuse.

Abuse is about power and control, not about how “nice” someone is. Truly, all the women mentioned in this blog post could be bratty, snotty, snobbish women. But that doesn’t mean that they should become victims of abuse.

Its popularity has been attributed to white supremacist Nick Fuentes (crazy that a white supremacist has a following large enough to make a trend, but I digress). Fuentes posted “Your body, my choice. Forever,” after election night. Instances of the phrase increased 4,600 percent on X during the last two weeks,

Its popularity has been attributed to white supremacist Nick Fuentes (crazy that a white supremacist has a following large enough to make a trend, but I digress). Fuentes posted “Your body, my choice. Forever,” after election night. Instances of the phrase increased 4,600 percent on X during the last two weeks,

What is unique about your role?

What is unique about your role? Can you share a memorable success story (while maintaining confidentiality) that highlights the impact of the work you do?

Can you share a memorable success story (while maintaining confidentiality) that highlights the impact of the work you do? In your opinion, what are the most pressing issues facing survivors of domestic and sexual violence today?

In your opinion, what are the most pressing issues facing survivors of domestic and sexual violence today? How has working at the agency impacted your personal views or perspectives on domestic and sexual violence (or stalking, or human trafficking)?

How has working at the agency impacted your personal views or perspectives on domestic and sexual violence (or stalking, or human trafficking)? Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

What do you believe is the most important aspect of your job as an advocate?

What do you believe is the most important aspect of your job as an advocate? Can you share a memorable success story (while maintaining confidentiality) that highlights the impact of the work you do?

Can you share a memorable success story (while maintaining confidentiality) that highlights the impact of the work you do? In your opinion, what are the most pressing issues facing survivors of domestic and sexual violence today?

In your opinion, what are the most pressing issues facing survivors of domestic and sexual violence today? How do you handle difficult situations? Personally and professionally.

How do you handle difficult situations? Personally and professionally.

What is unique about your role?

What is unique about your role?  Is there a particular service or program offered by Options that you find especially impactful or meaningful? If so, why?

Is there a particular service or program offered by Options that you find especially impactful or meaningful? If so, why? How do you practice self-care and prevent burnout, given the emotional intensity of the work?

How do you practice self-care and prevent burnout, given the emotional intensity of the work? What advice would you give to someone who wants to pursue a career in advocacy work for domestic and sexual violence?

What advice would you give to someone who wants to pursue a career in advocacy work for domestic and sexual violence?

“I have 2 (I couldn’t pick just 1). My first service choice is providing communities with awareness to help those impacted by abuse and trauma. My second pick is helping survivors and their fur babies. Organizations similar to our program will deny Survivors and their pets Shelter or Emergency Accommodations. As a result, a vast majority of survivor pet owners do not leave abusive associations and are susceptible to extreme physical violence including death.”

“I have 2 (I couldn’t pick just 1). My first service choice is providing communities with awareness to help those impacted by abuse and trauma. My second pick is helping survivors and their fur babies. Organizations similar to our program will deny Survivors and their pets Shelter or Emergency Accommodations. As a result, a vast majority of survivor pet owners do not leave abusive associations and are susceptible to extreme physical violence including death.”