In honor of Women’s History Month, Options will be highlighting exceptional women who have worked to combat gender-based violence. This first installation of articles will focus on the history of the anti-rape movement while honoring the brave women who first fought for justice.

Throughout most of history, rape was not viewed as a crime because women were considered property, and, therefore, without rights. Since women were viewed as objects, men took women as an act of aggression. In most cultures, marriages were arranged when the groom purchased the bride from her father. Rape was initially considered a crime only in terms of the property violation of another man. Punishment was delivered to a man who damaged the husband’s “property” (his wife) by rape. Very often the raped woman would be punished as an adulteress as well. For instance, ancient Hebrew women who were raped were considered “defiled,” and stoned to death.

The earliest documented efforts to confront and organize against rape began in the 1870s when African-American women, most notably Ida B. Wells, took leadership roles in organizing anti-lynching campaigns. The efforts of Ida and the women she worked with led to the formation of the Black Women’s Club movement in the late 1890s and laid the groundwork for the later establishment of a number of national organizations, such as the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Although women continued individual acts of resistance throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the next wave of anti-rape activities began in the late 1960s and early 1970s during other civil rights and student movements.

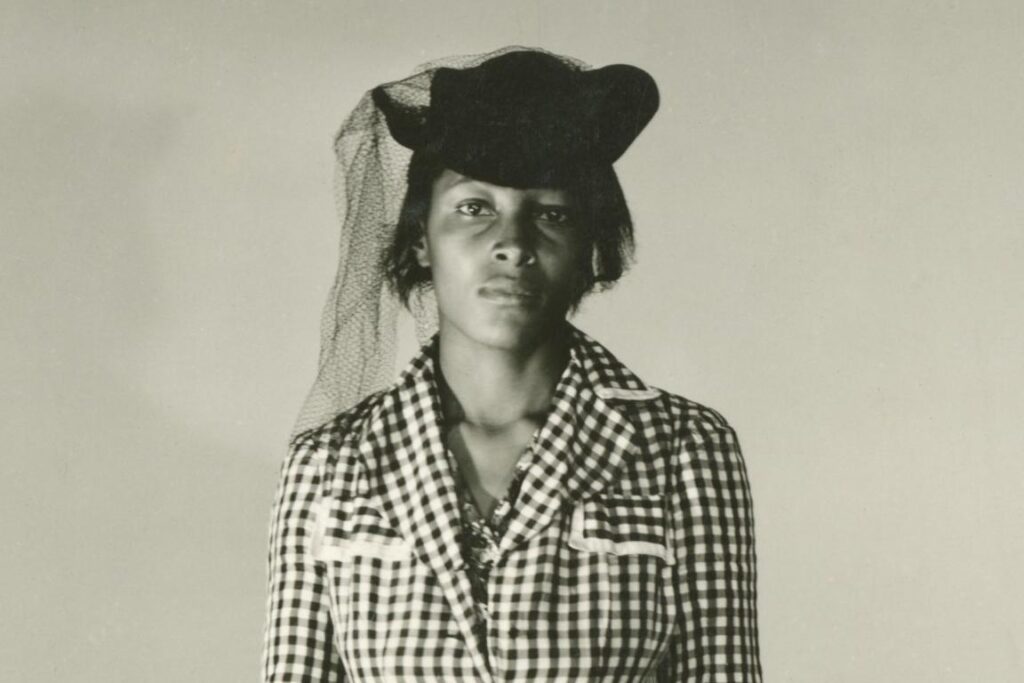

Recy Taylor was 24 in 1944 when she was kidnapped by six men while walking home from church in and gang-raped in the back of a truck. Even though one of the perpetrators had confessed, two juries refused to indict the accused. When the details of her story were reported in the Black Press, the NAACP sent Rosa Parks to the city where she was assaulted to investigate the matter. Parks then established the Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor, and the leaders of went on to organize the Montgomery Bus Boycotts. In 2011, the Alabama State Legislature officially apologized to Taylor for its lack of prosecution.

From the beginning of the anti-rape movement, education has been an important component of the response to sexual violence. Initial efforts focused on raising awareness about the prevalence and impact of the experience of rape, bringing forward the voices of survivors, and emphasizing the need for resources dedicated to these specific instances of assault. These educational activities established the foundation which eventually led to an improved criminal justice response to sexual violence, expanded healthcare services such as Sexual Assault Nurse Examinations (SANEs), and funding for a wide range of sexual assault prevention and intervention programs (especially the federal Violence Against Women Acts).

In 1971, Oleta “Lee” Kirk Abrams co-founded the nation’s first rape crisis center. Abrams founded the nonprofit “Bay Area Women Against Rape,” which still serves hundreds of women each year from its Oakland offices. She was inspired to create the nonprofit after her 15-year-old foster daughter was raped at Berkeley High School.

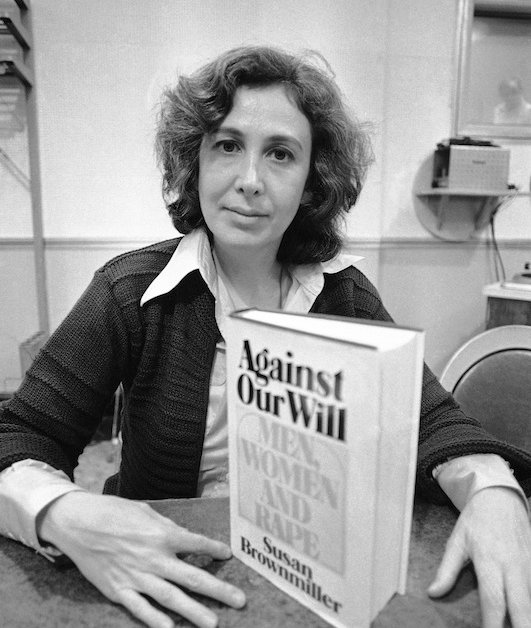

A few years into the anti-rape movement, Susan Brownmiller, an American journalist and activist, wrote her book “Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape.” In her book, published in 1975, Brownmiller argued that rape had been previously defined by men rather than women, and that men use it as a means of perpetuating male dominance by keeping all women in a state of fear. To research for her book, she spent four years investigating rape. She studied rape throughout history and collected clippings to find patterns in the way in which rape is reported in various types of newspapers. She also analyzed portrayals of rape in literature, films, and popular music, and evaluated crime statistics. The New York Public Library selected “Against Our Will” as one of 100 most important books of the 20th century.

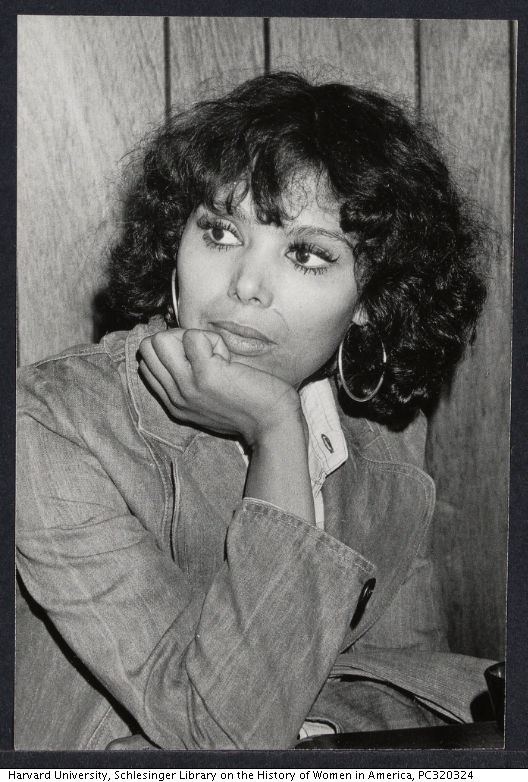

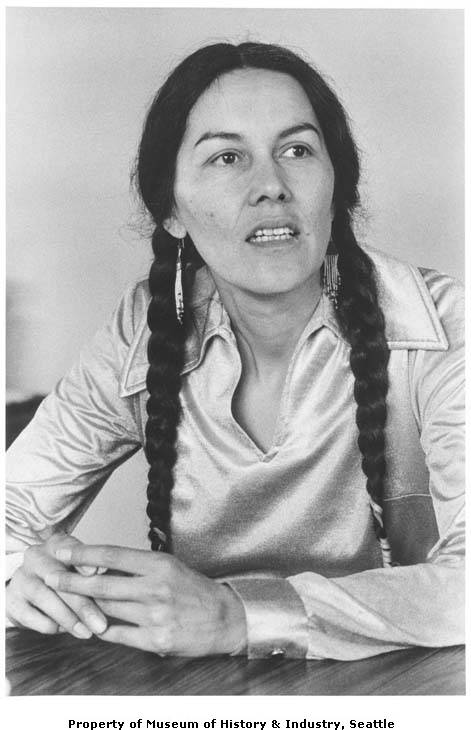

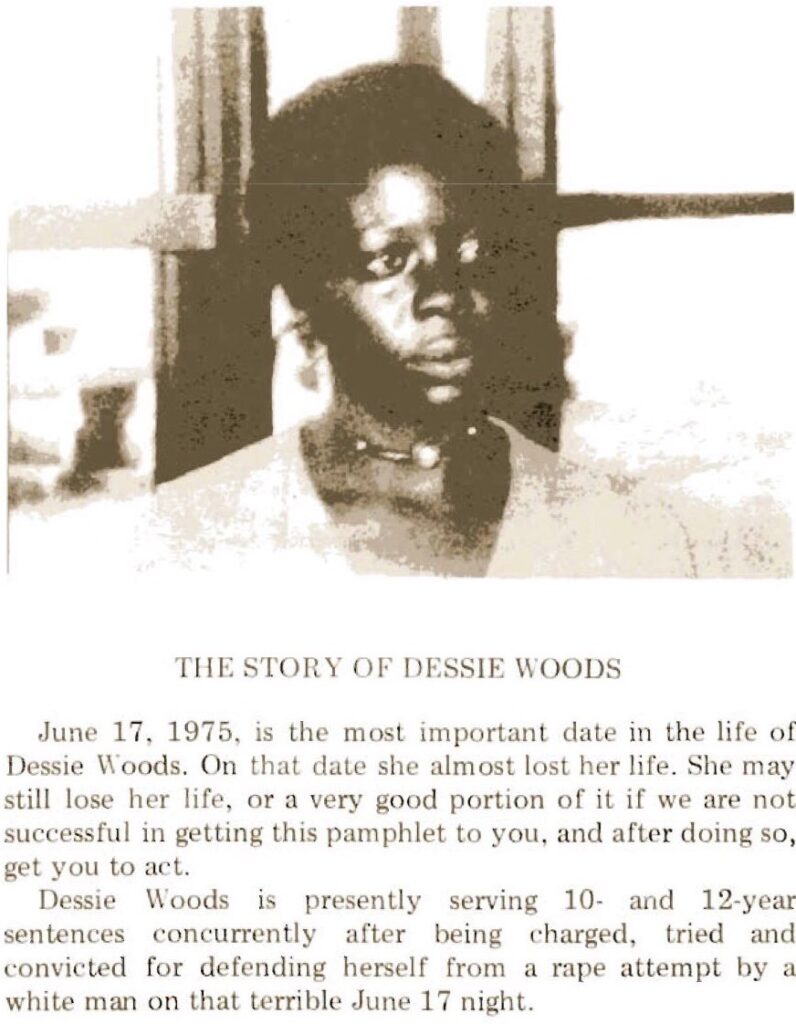

Organizing efforts during this movement also brought national attention to the imprisonment of several women of color who defended themselves against the men who raped and assaulted them. Inez Garcia in 1974, Joan (Jo Ann) Little in 1975, Yvonne Wanrow in 1976, and Dessie Woods in 1976, are all victims of rape or assault who fought back, killed their attackers, were imprisoned, and brought the issue of rape into political organizations that had not historically focused on rape. Dessie Woods was eventually freed in 1981, after a long and difficult fight for her freedom.

Even after all of this progress, women today are typically left to struggle with the trauma that the act of violence and violation has inflicted on them — trauma which lasts their entire lives. Yet despite the statistics of violence against women worldwide, stories of individual women and their acts of courage, hope, and resilience continue to emerge in many ways from hashtag discussions on social media to high profile sexual assault and rape cases where dozens of women come forward to finally force powerful predators like Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby to face the consequences of their acts of violence and abuse.

Having been through the pain of unspeakable violence and overcoming their traumas, many survivors become women’s human rights activists who show incredible courage in coming forward with their stories in a world that habitually victim-blames women and girls. During the month of March, Options hopes to continue to highlight the stories of women who have made a difference in the world around sexual and domestic violence.

Keep up with Options blog posts during March to see more stories of women leadership in the field of advocacy.

If you need any additional information, have a question, or a concern, feel free to reach out to Options at our 24-hour toll-free helpline 800-794-4624. You can also reach an advocate via text by texting HOPE to 847411 or click 24-Hour Chat with Options.

Written by Anniston Weber